One Model to Rule Them All: Cross-platform Mobile Test Automation at BlaBlaCar

Apps should feel native.

This axiom of mobile application design is one of many best practices that we employ at BlaBlaCar. While today we do offer four interfaces to our community, including our desktop and mobile websites and native iOS and Android apps, we strive to provide our members with a mostly-consistent experience across all of them.

But different platforms are, well, different. Mobile platforms, especially, can have wildly different design guidelines that lead to differences that, yes, “make apps feel native” but also make it a bit more complicated to test if you don’t want to repeat yourself.

Our Quality Assurance Specialists are a limited resource, so we try to automate as many repetitive tasks as we can. The problem we then face is that, even with automated tests, we have two different mobile products, which can in turn necessitate writing the same tests twice.

A challenging context

We were starting from scratch, with very limited resources and more than 3 years of features that were being tested exclusively by hand. It was a daunting problem to solve, but we realized that, thanks to the fact that our iOS and Android applications have essentially the same workflow, things didn’t have to be so bad. So we gave ourselves a bold goal: build a single end-to-end test framework for both platforms. More specifically, we wanted to establish the simple principle that each test written should be executable on both platforms. This required a robust design, since we wanted to build something that can be easily extended and maintained as the product grows.

We named it the Qualcium project: a cross-platform end-to-end test framework for our native mobile applications. Built on WebdriverIO, with Mocha on top, Qualcium is basically a JSON Wire Protocol client for Appium running on Node.js.

From Page Models to Neutrons

In order to implement a flexible architecture, we decided to adopt the Page Object pattern, another widely-used best practice popularized in web test automation. The basic idea behind the page object pattern is to wrap low-level commands, usually with a class, exposing methods at the user level. For instance, imagine a login form view with email and password fields plus a submit button. In JavaScript (ES2015), such a class might look like this:

class Login {

// Some user-level methods...

login(email, password) {

return this.setEmail(email).setPassword(password).submit();

}

setEmail(email) {

this.driver.element(this.constructor.EMAIL_INPUT).type(email);

return this;

}

setPassword(email) { ... }

submit() { ... }

forgotPassword() { ... }

}

// ... and some locators to define interface elements.

Login.EMAIL_INPUT = '#email';Done? Well, not quite. It would be so convenient if elements could be located in either app using the same identifiers, and if the same Appium commands would run flawlessly on both iOS and Android, but this is generally not the case. Today, we don’t require this kind of “element ID” synchronization across our two mobile teams, since we want to move as quickly as possible, and introducing this requirement into such a high-velocity development process would only slow everyone down at this phase. We want to test the application we deploy, as-is, without requiring special tweaks or interventions from our busy mobile devs.

Fortunately, our model handles these discrepancies by extending the base class:

class Android extends Login { ... }

// No ID on the Android app :(. No problem, XPath for the rescue!

Android.EMAIL_INPUT = '//android.widget.EditText';

class IOS extends Login {

setEmail(email) {

// On iOS we can directly inject the value, and it's way faster!

this.driver.element(this.constructor.EMAIL_INPUT).setValue(email);

return this;

}

}Great! Now we can take into account platform specificities while having most of our code shared. Now, what if we want to reuse our login form model for a signup form? We had to rethink the Page Object pattern and come up with a new paradigm. Using a mixin-like construction, we can inject new methods from the SignUp class into parent classes to create new classes which benefit from previously-implemented behaviors and locators. SignUp works as an interface with default methods:

const SignUp = Page => class extends Page {

setUserName(name) { ... }

setBirthdate(date) { ... }

}

// `login` is an object which has an IOS and an Android class as members

class Android extends SignUp(login.Android) { ... }

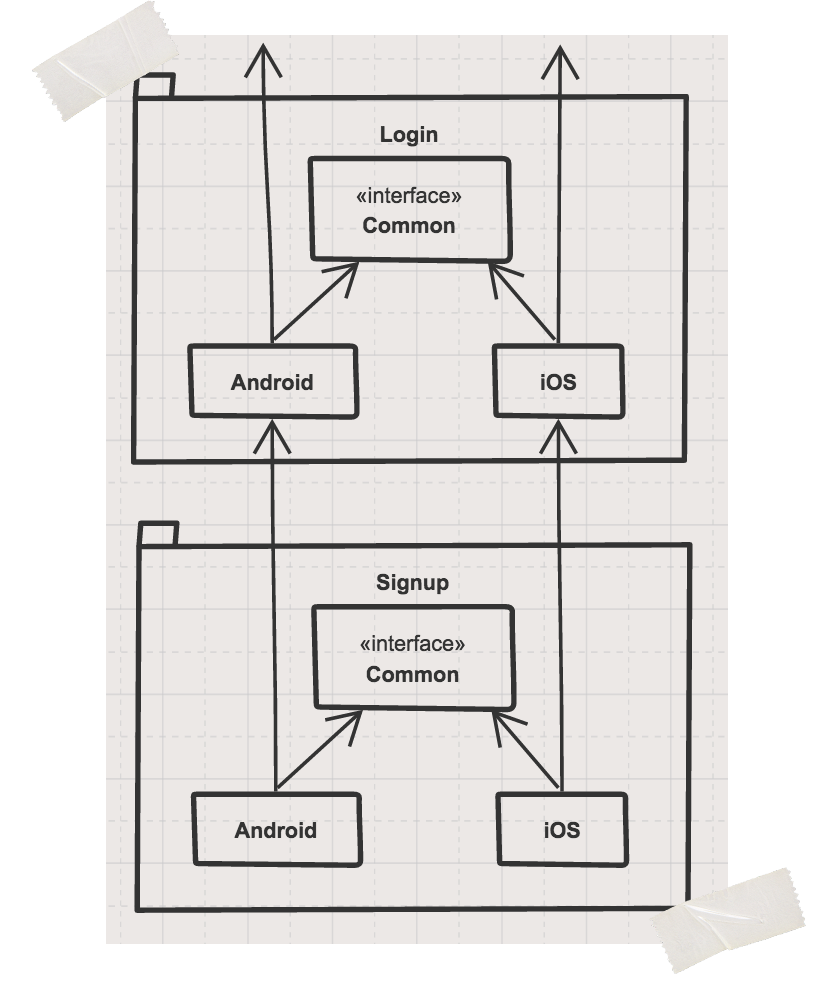

class IOS extends SignUp(login.IOS) { ... }We call this construction a Neutron in Qualcium. It is a component comprised of one interface and two classes, each one representing a platform, just as the subatomic particle consists of one up quark and two down quarks. Neutrons are modules, and they adopt a common standard:

Using this standard allows us to create reusable Neutrons from other Neutrons while also addressing our code maintainability requirement.

Fluently describe flows

One of our goals when designing such models is to have them provide sets of methods that represent high-level actions, avoiding or hiding less useful low-level actions as much as possible. Additionally, we want Neutrons’ interfaces to abstract away divergent behavior, describing what the service offered by the application does, not how it works. Last but not least, we want the relationships between these Neutrons to reflect the user’s journey through the application.

To achieve this, all Neutrons’ methods return an object that belongs to a Neutron. Let’s consider three different use cases.

After filling in a member’s credentials — simple element manipulation actions that stay within a single view — we want to continue to use the same service and context:

setEmail(email) { ...; return this; }

setPassword(password) { ...; return this; }In cases involving navigation between views, we might want our current Neutron method to return another Neutron’s object. For example, pressing the “Forgot Password” button leads to another view that allows us to change our password. That means a new class that belongs to another Neutron needs to be instantiated… but which one? It actually depends upon the platform, so we introduced a spawn method to take care of it:

forgotPassword() { ...; return this.spawn(forgot); }class Android {

spawn(Neutron) { return new Neutron.Android(...); }

}

class IOS {

spawn(Neutron) { return new Neutron.IOS(...); }

}Finally, when we submit the login form, we would expect to… eventually be signed in? What if we don’t properly enter our credentials? We do not want Neutrons to be responsible for our mistakes:

submit() {

...

return {

success: this.spawn(dashboard),

failure: this

}

}This example is pretty common, but applying it to more complex cases is also very useful. As of this writing, BlaBlaCar’s apps are distributed in 22 countries, and some behaviors differ from one country to another. Creating objects which give a closed set of potential flows enables us to model a variety of country configurations.

In the end, the way Neutrons are linked together mimic the product workflows. This becomes even more apparent in our scripts, which use these Neutrons via a series of chained method calls, revealing a nice fluent syntax:

...

// Gollum tries to log in but fails.

.login('gollum@blablacar.com', 'mYpr3ci0uS').failure

// Stupid password.

.setPassword('mYpr3ci0u5')

.submit().success

// Yay!Learnings

Qualcium is still a very young project. We are currently scaling Neutron coverage of both of our iOS and Android applications at the same pace.

Bootstrapping an architecture to build models which work for both platforms was quite challenging. We came up with different design solutions, and we’ve found that this is the one that best fits our specific needs. Such patterns could even be adapted and applied to our desktop and mobile web automation - more on that later.

Writing such modules might seem at first like overkill or over-abstraction, but we believe our approach is ultimately very rewarding. Once comfortable with it, creating new components becomes intuitive, though consistency and simplicity is key.

One caveat: sharing a common model for both of our apps works for us because it fits how these products are designed at BlaBlaCar. Those tasked with testing a mobile app that exists on multiple platforms may need to consider a different approach if they diverge in more profound ways, or if the feature set or workflows are fundamentally different.

In many other cases, however, creating Neutrons (or adopting a similar pattern) might require only a little more work. You may just need to rethink how to unlock the power of the page object pattern.